Michael Savage was born in the Tatong district in

1872.

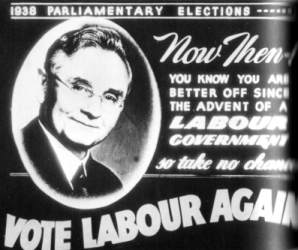

His other claim to fame is being Prime Minister of New Zealand from 1935 until his death in 1940.

Source of the following: The first two chapters of “From

the Cradle to the Grave”, a biography of

Michael Savage by

Barry

Gustafson, Professor of Politics. These give an

excellent account of the early settlement of Tatong.

What follows is very much abridged from these two chapters, with

a little information added from other sources.

There is far more information in the book itself, as well as the

rest of Michael Savage’s life.

Thanks to Professor Barry Gustafson for his kind permission to

reproduce here this abridged version of his work - Andrea

Stevenson, for the Tatong Heritage Group.

Michael’s parents Richard and Johanna Savage (nee Hayes) were Irish born. They struggled to get by in 1850’s Melbourne, where thousands lived in tents and shacks.

The Sydney Morning Herald said of Melbourne “a worse regulated, worse governed, worse drained, worse lighted, worse watered town of note is not on the face of the globe.”

Richard Savage rowed a two-oared passenger ferry on the Yarra. Along the northern bank was an industrial belt of slaughterhouses, fellmongeries, tanneries, tallow factories, breweries and flourmills. Their effluent went into the river, along with garbage and excreta from the shanty town. The Yarra was the city’s water supply.

Their first child died of diphtheria. With Melbourne in an economic slump, the Savages decided to seek health and independence by farming.

They travelled by bullock wagon on a rough dirt road; the railway was not to reach Benalla until 1873. Joanna, nursing their second child, was eight months pregnant.

|

|

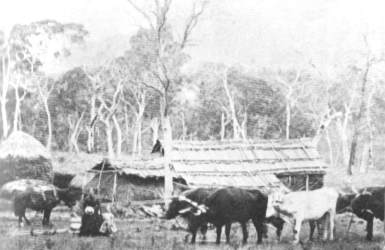

Typical selection in North East Victoria, 1875. |

In 1861 the Victorian government started subdividing the leasehold runs of the squatters for selection. In 1862 Richard Savage selected an allotment of 72 acres in the parish of Tatong, with Holland’s Creek forming the back boundary. Most selectors purchased on terms, but Richard bought his allotment outright, giving him freehold but little working capital.

Selectors were legally obliged to crop the land. At that time the area was heavily wooded plains and hilly bush country, and the land had to be cleared by ringbarking, felling and burning. Stumps had to be moved before the single-furrow plough could cut through. Crops were harvested by hand scythe, and threshed by a hand flail.

Richard Savage fenced his property and built a hut of rough slab walls, bark roof, mud floor, and adjacent fireplace for cooking and heating.

Over the next ten years Johanna gave birth to seven more children. All survived infancy, better than the usual survival rate of her contemporaries.

Selector’s Woes; Clearing Tatong

The squatters resented newcomers laying claim to ‘their’ land. The selections were more suited to grazing than cropping, and at mostly less than 200 acres, were too small for either.

Tatong was too far from markets. In winter the dirt road to Benalla was often impassable, even twenty horses failing to pull wagons through the axle-deep mud.

In 1864 fire destroyed Richard Savage’s second wheat crop (already ruined by red dust parasite) and most of his fencing. His 3rd crop in 1865 was flattened by a violent storm. The drought that scorched out the 1869 crop was followed in June 1870 by one of the largest floods in the district’s history. A few months later a tremendous hurricane swept the countryside, wreaking havoc and perpetuating the flood. In October, five months after land first vanished under water, there came ‘more rain; more floods; damage; more destruction; more narrow escapes; more disappointment.’

There was no crop in 1870. Hordes of rabbits and kangaroos and plagues of grasshoppers competed in stripping the countryside of vegetation. In the early 1870s wheat prices slumped.

Most selectors were forced to borrow, but at first the banks were forbidden by law to lend to settlers. Many settlers during the 1870s and 1880s paid extortionate interest rates of 20 to 25% to merchants, graziers and loan sharks, whose ulterior motive for lending was often to foreclose on the property after it had been cleared and improved.

Richard Savage earned a few shillings doing odd jobs such as fencing, dam-sinking, drain-digging, clearing and shearing for the squatters and graziers.

Johanna fed and clothed her large and growing family as best she could, making household goods and tending the stock. With the nearest school and church at Benalla, Johanna started to teach the children to read and write.

When Johanna was ill, a girl helping her dropped 1-year-old Joseph, fracturing his spine. He was crippled and hunchbacked for life.

Despite all this, Johanna’s son Rowland remembered: “Mother taught us to step-dance soon as we could walk, the Irish Jig and so on, at which she was no mean performer.”

The little Savages worked on the farm from the earliest age possible, chopping wood and carting water, digging drains and fencing.

In 1873 a neighbour, Dan Ginnivan, aged 33, was thrown from his horse and killed. He left a widow and three young children, whom Richard and Johanna befriended. One of the children later married Michael’s brother Rowland.

Michael's Birth; The Rothesay Selection

Michael Savage was born on March 23rd 1872, during a heat wave. For days the temperature reached 110F (43C) in the shade. A neighbour, Eliza Chivers, delivered Johanna’s eighth and last child; in Irish parlance, the ‘tupenny’ child.

On 17 May 1872, a few months after Michael’s birth, his father began to purchase on terms 176 acres of newly opened land. This was at Rothesay, some seven kilometres North-west of Tatong. Savage’s first farm, which he now sold, was better land and was to become even more desirable with the development of the dairy industry in the 1890s. But it was prone to flooding, and 1872 was the third successive year that it had been under water for two or three months.

It was also surrounded on all sides by the freehold blocks of the big graziers Splatt, McCullough and Colclough. There was nowhere for Savage to expand, and by 1872 he was convinced that his salvation lay in a larger mixed farm and crop rotation.

The move to Rothesay took advantage of adjoining crown land, and Savage was the first selector on the new block. He hoped that each of his seven children, upon turning 18, would select 320 acres adjacent to their father’s farm. Rose and four brothers later obtained allotments, but only Rose’s 392 acres were subsequently paid off.

The Rothesay selection consisted of three allotments, of 72, 66 and 14 acres. Included was an area set aside for a proposed extension to the railway line. The property was on a secondary road, which became Savage’s Lane, linking Tatong to the main Benalla-Samaria road. Savage completed his purchase of the 72-acre section in 1884, but lost the other two.

Illness and Death of Johanna Savage

The new selection was heavily wooded and difficult to clear, and Johanna was ill from an attack of rheumatic fever. In 1876 Dr Joseph Henry from Benalla diagnosed heart trouble and ordered at least another three months’ complete rest.

The two eldest children, Rose 15 and Richard 14, left school to help on the farm and to care for their sick mother and the five younger children.

Rowland recalled, “I mind well hearing Mother say then as always: ‘We are not half thankful enough to God for all He does for us’. I was only six, but for the life of me I couldn’t see what Mother had to be thankful about. I now realise her deep appreciation of Father’s good qualities. He didn’t smoke, drink or gamble, and was an estimable husband, father and citizen.’

Johanna recovered but a little over a year later she suffered appendicitis. Before Lister’s discoveries, opening the stomach meant almost certain death. Johanna was ill for weeks, lying in bed in the heat of mid-summer, surrounded her family. She was 39 years old; her children aged 16, 15, 13, 11, 9, 7 and 5. Rowland recalls: “Doctor Henry was in constant attendance, and everything possible was done under the circumstances, but Mother developed excruciating pain. I shall never forget it—the agony of peritonitis. No hospital, and little was known of general anaesthesia and major surgery. Her screams! In her few easy moments, with no thought of herself, saying always ‘God is good’ she tried to console and advise Father as to what he should do for himself and the seven children after she had gone. One of her own countrymen, Reverend Father Kennedy of Benalla, administered the last sacraments.

“Before the dawning on 10 February 1878 the soul of our dear mother, a very fine, game little woman passed from this earth, with our broken hearted father, Rose, Richard, Hugh and Mrs McNaughton kneeling around her deathbed, praying. Mick and I were not told until morning, along with Willie and Joe. Mick was not quite six years old then.”

1878 continued to be a dismal year for the Savage family. Good harvests early in the year were negated by low grain prices. Then heavy rains and flooding in October and November led to the 1879 harvest being the lowest yield on record. The newspapers noted that ‘from Benalla to the Murray nothing but sheer ruin stares many in the face’.

Richard Savage, struggling to get his new farm established, failed to make the required improvements on part of his Rothesay selection and forfeited about half of it.

Nevertheless, in March 1880 Rose paid £24 to take out a licence on a selection of 392 acres next to her father’s farm. Over the following years the Savage family cleared, fenced and cultivated this property, which was eventually combined with Richard Savage’s farm and worked more and more as a dairy farm. Rose continued to live with and care for her father and six younger brothers, the lively teenager becoming a substitute mother.

Before Victoria introduced the first comprehensive system of free, compulsory and secular education in 1872, many Australians remained illiterate.

Richard Savage was an educated man who acted as election poll clerk for the Rothesay district, and wrote letters for neighbours unable to read or write. Within months of the passing of the 1872 act, he organised a petition and sent off several letters requesting the government to establish a school at Rothesay. He pointed out that there were six families with twenty-two children, including the seven young Savages, under the age of fourteen in the district. He arranged for a temporary school building opposite the farm on which the Savage family was itself in temporary residence. The chairman of the local Education Board of Advice wrote that ‘Mr and Mrs Savage of Rothesay near Benalla—most respected farmers’ were prepared ‘to receive a female teacher and give her the necessary accommodation’ in order to get the school started.

In August 1874 the Rothesay school, State School Number 1438, was opened. The initial twenty pupils, sitting in four seven-foot-long desks, were crowded into a room twelve feet by eleven feet and with a height of seven feet. One of the first teachers described ‘the heat at times quite oppressive and fatiguing’.

In 1879 a new school building, still so small that Michael later recalled ‘one could hardly turn round in it’, was erected. His father organised a dance to mark the opening. This started at 6.30 p.m., with the dancing and singing to violin and concertina going on until daybreak, when a children’s picnic was held. In this year 7-year-old Michael started school.

Pioneer Teacher - Sarah Ann Brown

More important than the new schoolroom was a new teacher; 47 years later Michael visited Rothesay to see her. Sarah Ann Brown was typical of the young women teachers who brought literacy to rural Victoria, and just 20 when she came to Tatong. Remembered as firm but very kindly, she was very particular about correct grammar, spelling and punctuation.

For several years Sarah Ann lived in the lean-to at the back of the school. She recalled Mick coming to school with flour and dough on his fingers and clothes after having made his own lunch of damper or scones.

On marrying, Sarah Ann converted to Catholicism, and brought up her own large family. After the death of her husband she ran the farm, and subsequently raised her grandchildren from infancy when her daughter-in-law died.

By 1879 the Savage family had moved 2 ½ kilometres away to their own Rothesay selection. Michael and his brothers daily picked their way bare-footed along a track through the thick scrub, pieces of paper pinned to the trees to stop them becoming bushed. They often played bushrangers, for 1878-80 were the years of the Kelly gang’s greatest notoriety in the district.

Ned Kelly and Michael Savage had much in common – both were the sons of poor Irish-Catholic settlers of the Benalla district. Both saw one parent struggle to maintain a large, young family after the death of the other parent. Both rebelled against the system that suppressed them. But whereas Kelly drifted into crime, and died on a Melbourne gallows on 11 November 1880, Savage went on to reform New Zealand. Years later Michael Savage observed, ‘Though I was born in the same district in which Ned Kelly did his bushranging, I did not inherit his methods.’

Richard Savage continued to be the parental mainstay of the school, striving to keep it from closing or being changed to a half-time teaching post. In 1882 Richard Savage wrote that the average attendance of 16 or 17 pupils over the preceding winter months was misleading because of the ‘flooded state of the roads’, which had stopped children walking to school. The decline in attendance at the end of the previous summer had been because ‘a great many of the children could not attend through blindness caused by the unusually dry summer’. (The blindness was trachoma infection, "sandy blight", brought to Australia with European settlers and widespread in poor housing conditions.)

The Rothesay School became half-time in 1886, closed down temporarily in 1901, and was burnt down by a lunatic Italian and an Indian Hawker in 1905.

In 1884 Mick obtained his “certificate-of competence” and left school to help Rose about the house and his father about the farm.

By the early 1880s settlement at Rothesay was sparse. Most of Michael’s brothers were young men, working and playing football. Mick spent much of his spare time with Joe, who was unable to walk far. The summer of 1884 was very hot, and the storms which finally got rid of the fires and grasshopper hordes blew down trees. Kangaroos, crows and cockatoos left little grain for the farmers to gather, and in March 1885 a run of early frosts destroyed the district’s potato crops.

During winter months, when roads were impassable and people shut indoors, rural families were dependent on each other. In summer there was more widespread contact, with visits to Benalla and picnics and sports meetings, such as the annual gathering at nearby Samaria.

The Savage’s neighbour Joe Whelan taught all the Savage boys to hunt, track, and break-in good horses. A widower with a young family, Whelan was illiterate, and on Sunday afternoons would visit to hear Richard read the newspapers. Joe and Mick also listened; to the exploits of the Kelly gang; to pathetic stories of destitute old men and women, the sick and unemployed; to lurid cases of assault, rape, child abuse, murder, and domestic violence and tragedy; to barely understood articles on land selection, protection or free trade, the rise of unions, home rule for Ireland, international and domestic politics and economics. The papers mirrored and indeed highlighted the harshness of the wider world.

The summer of 1885/86 was one of unprecedented drought in the Benalla district. Ploughs stood idle, cows stopped producing milk and many selectors faced insolvency. Selectors’ youngest sons were encouraged to seek employment elsewhere. Older boys joined the itinerant labour force of shearers and station-hands. Younger lads, especially if they were reasonably bright and hard-working, sought employment in a shop or office.

In 1886, aged 14, Michael Savage secured his first job in a Benalla general store. Michael was to work for its owner, Antonio Ball, for the following seven years.

In the 1880s Benalla was a rough frontier settlement. It was divided by the Broken River, which was described at the time as “a sluggish stream, broken up into muddy and stagnant lagoons.” Neither roads nor footpaths were sealed or drained. Dusty in summer, in winter after a few heavy showers the road turned to putrid mud.

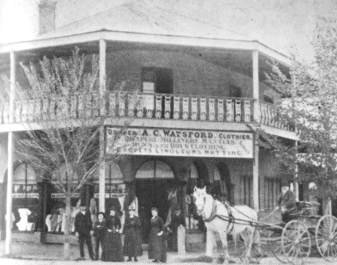

Ball’s shop was in a large two-storeyed building at the corner of Bridge and Carrier Streets, originally swampy land and inclined to flood badly.

In front of the shops were open drains,

hitching posts and water troughs. There was no street lighting.

The population of the town was about 1,700, one quarter of the

Benalla Shire, 27% Roman Catholic and 20% born in Ireland.

Benalla had a railway station, a post and telegraph office, a

police court, a Rechabite Hall, a Mechanics’ Institute and

Library with 150 books, 2 newspapers, 2 state schools, 2 private

schools, 4 banks and 5 churches. It also had a brewery, several

wine and spirits shops and 17 hotels.

One of the wine and spirits merchant licences was held by Antonio Ball, who had sold clothing, shoes, millinery, drapery, hardware, furniture, crockery and groceries. Early in 1886 Ball advertised a complete clearance sale as his landlord had advertised the premises for sale. In June Ball received a reprieve and bought in new stock, limiting himself to drapery, wines and spirits, and just a few grocery items necessary to meet the requirements of his liquor licence. He also hired a new assistant, Michael Savage.

Tony Ball was accomplished actor and singer, and widely read. He was involved in community affairs as founder of the Benalla fire brigade, organiser of children’s picnics and member of the rifle club, all activities in which Michael Savage later became involved.

At first Mick was paid 5 shillings a week and keep. He swept and dusted the store, cleaned the windows, unpacked cartons, disposed of rubbish, stocked shelves, served at the counter, delivered groceries, parcels, and bottles of wine and spirits, mucked out the stable, and groomed and fed the carthorse. He slept on a stretcher in the back of the shop and had meals at the ‘Five Alls’ pub. The “Five Alls” is an old English country sign, representing five figures: the monarch, who governs all: the bishop, who prays for all: the lawyer, pleads for all: the soldier fights for all: and the farmer, who pays for all. The ‘Five Alls’ was patronised by Kelly sympathisers.

Shop hours were long in Benalla during the l880s. In 1886 young Mick was usually working in excess of 90 hours a week. An Ensign editorial deplored the strain placed upon young shop workers, and the clergy were concerned that young male shop assistants were desecrating the Sabbath by indulging in sport in their one free day.

In December 1887 Ball selected 820

acres of land at Tatong and the following January sold his

drapery shop to A. C. Watsford, of Melbourne. He kept his wine

and spirits licence, and a fortnight later opened a liquor shop

in half of the old St George’s adjoining the corner drapery

shop. He was at his selection for lengthy periods and Michael,

nearly 16, began to take more responsibility in the shop.

In December 1887 Ball selected 820

acres of land at Tatong and the following January sold his

drapery shop to A. C. Watsford, of Melbourne. He kept his wine

and spirits licence, and a fortnight later opened a liquor shop

in half of the old St George’s adjoining the corner drapery

shop. He was at his selection for lengthy periods and Michael,

nearly 16, began to take more responsibility in the shop.

Mick improved his formal education, Ball introducing him to various commercial skills. In 1889 Thomas McCristal, a well qualified teacher, started his Christian but ‘strictly unsectarian’ Benalla College, later known as the North Eastern College. McCristal classes included bookkeeping, writing and arithmetic, and evening preparatory classes for matriculation.

The Mechanics’ Institute, which was supposed to help educate workers, had ironically become elitist in Benalla, its membership made up of doctors, lawyers, bankers and businessmen.

A branch of the Australian Natives’ Association formed in Benalla in 1882. There is no evidence that Michael Savage belonged to it, but later in life he often quoted its principals. Established in Melbourne in 1871, ANA membership was restricted to Australian-born males over 16. It was a friendly society providing benefits to its members in sickness, disaster or death ‘as a matter of right… not begging.’ The ANA advocated pride in being Australian; the assimilation of new immigrants; the federation of Australia into one nation; one person, one vote; women’s suffrage; a legal minimum wage; irrigation; afforestation; conservation of natural resources; maternal and infant welfare; and national defence. Membership was open to Jew, Catholic and Protestant.

About 1890 sectarian bitterness in Australia increased. Catholic priests prohibited inter-marriage, and were attacked in turn by dogmatic Protestants. Michael was well aware that his Catholic background could be a social disadvantage.

At 18 Michael was more interested in sport than religion. All the Savage boys, with the exception of crippled Joe, were fine athletes, often mentioned in the local newspaper reports of Australian rules football and races and field events. Mick went shooting, swam naked on Sundays in the swimming hole near the railway bridge, and fished in the Broken River. He played some football, most games being played on Saturdays when he was working. He exercised in a local gym and won trophies for boxing and weightlifting. He enjoyed New Year’s Day race meetings, though he rarely placed a bet, and he gave exhibitions of step-dancing and Irish jigs.

Little is known of girlfriends during Michael’s teenage years. Young men outnumbered young women in Benalla in the 1880s, some returning to England or Ireland in search of brides. Few had the inclination or the means to settle down. A wage of £1-£2 a week was barely sufficient to cover one’s own needs, let alone those of a wife and children, and Michael was only earning £2 by the time he was twenty. The local newspapers frequently reported the death of some young man leaving a wife and three or four children totally unprovided for. As depression deepened at the end of the 1880s, the number of marriages dropped sharply to even lower levels. Over a third of Australians in the late nineteenth century never married.

Local legend associated Mick with Kate Kelly, younger sister of Ned. Savage recalled often serving Kate and her mother in the store, Kate being about the same age as Rose Savage and Sarah Ann Brown. The legend goes that Kate later left the district to live with Michael Savage in New Zealand. There is no truth in it; each moved independently to sheep stations in New South Wales, and Kate, who had married William Foster in 1888, had a family and was drowned in Lake Forbes in 1898.

In 1890 Tony Ball contested the Benalla Shire elections. He accused the incumbent councillors, mostly wealthy land-owners, of having formed a ring ‘to plunder the Central Riding’ using shire funds to build bridges and improve roads near their farms. He and the Ensign wanted those funds used in the town itself to improve the unsanitary drainage, provide a good water supply, erect street lamps and build a decent crossing of the river. The whole town had open drains into which people deposited sewage. In a poll restricted to rate payers, Ball was sixth out of six candidates for three positions, obtaining only 79 votes.

In 1891 Michael Savage joined the Fire Brigade, and becoming very active as a fireman and in the brigade’s gymnasium. The Benalla fire brigade consisted of twenty-five men and practised three nights a week, training including jumps from a height of six metres into canvas escape sheets. Firemen received 2 shillings for the first hour at a fire, then 1s. 6d. for each hour thereafter, and for the official monthly practice.

In July 1892 Michael Savage was elected secretary of the fire brigade. He organised the novelty sports in September, incidentally winning the firemen’s race. He also arranged the purchase of a new fire-engine, which arrived in January 1893.

In October 1892, representing the Fire Brigade, he was elected as treasurer to the ten-person committee raising funds for the Wangaratta hospital and the Beechworth Benevolent Asylum. The charity function attracted over 1000 people and raised a net profit of £27.

Savage was horrified by the problems faced by hospitals and asylum in a society in which there was no government-funded social welfare. Many of those incarcerated in the Beechworth Asylum at that time were not lunatics, but people with no one to look after them and nowhere else to go – the ill, deformed, bedridden, or alcoholic. In the 1880s and 1890s Benalla removed undesirables from its streets by charging then with lunacy and getting them committed to the Beechworth Asylum.

Meanwhile back on the Selection

At the start of the 1890s, Rose, young Richard, William, Hugh and Joe all applied successfully for selections of land near their father’s farm. In 1891 Rose married Edward Cain and started farming Kilfeera Swamp near Benalla.

Young Richard won the contracts to deliver mail to and from Benalla and Tatong via Rothesay, and to and from Tatong and Lima East via Moorngag, Samaria and Swanpool, for a total of £8 per annum.

Rowland, unsuccessful in getting a selection, took his earnings of 8-10s. a day as a rabbiter and with a partner bought the large Cobb and Co. livery stables at the back of the prestigious Benalla Hotel. He serviced coaches travelling along the Sydney-Melbourne road, hired out horses and buggies, broke in wild horses on contract, and offered stallions for stud. Subsequently he sold out to his partner, bought a hotel and established small brewery at Yackandandah, further north.

Butter Factories and Creameries

Following the discovery of refrigeration and ammonia-chilled railway vans, Richard Savage senior became an ardent advocate for a butter factory in the district. He saw that dairying would transform farming in the Rothesay area. However his advice that the district should unite to set up one butter factory with a number of contributing creameries was ignored. Instead, competing small factories were established at Tatong, Swanpool and Benalla. Richard Savage, now over 60, reluctantly supported the decision of his neighbours to ‘go it alone’ and build the Swanpool factory. By the end of 1891 this was the first butter factory to operate in the Benalla district, with Richard Savage as auditor.

On 9th January 1891 Michael’s only sister

Rose, who had raised him from when he was 5, died in childbirth.

She was 31 and had been married 11 months. Dr John Nicholson was

in attendance but there was apparently little he could do; the

baby’s exit was blocked by the placenta, which ruptured. Rose

bled to death in screaming agony; the baby was stillborn.

Rose’s funeral ‘was one of the largest ever attended in the

district’, according to the Benalla Standard.

In December of that year Michael’s crippled brother Joe, who despite his disability had become a respected farmer, died of pneumonia aged 21. From that time on Michael Savage used the name Michael Joseph Savage.

The period 1891-93 was a watershed in Australian history. The 1880s had been marked by frenzied speculation, fuelled by overseas loans, government expenditure on railways and other public works, easy finance. 70,000 immigrants arrived in Victoria in the last half of the decade. Business fraud and political corruption were rife. The Victorian Parliament became ‘a sort of land speculators’ club.

Inevitably the crash came. By 1892, 41 land and finance companies in Melbourne and Sydney, with liabilities of £25,000,000, had failed. In January 1893 the Federal Bank defaulted and in April, as the panic spread, 12 other banks closed. At the end of April 1893, the National Bank suspended business. It was the bank principally used by the business people of Benalla and also by many farmers. Large numbers of selectors flocked to town only to find that the Victorian Government had closed the colony’s entire banking system for a week to allow reconstruction.

Farm income had fallen marked since 1891, with a very wet winter and infestations of wombats and locusts. In 1892 rust destroyed most of the wheat crop. Banks called up loans and foreclosed on mortgaged property. The government started pressing selectors for arrears in rent, and many forfeited their selections. The depression was followed by seven years of drought from 1896-1902, the worst drought recorded in Australian history. By the end of it stock numbers halved. Most of the Samaria district fell into the hands of one man, William McKellar, who had the Lima and Samaria homestead blocks, including most of the water.

In 1898 Richard Savage, after almost forty years of struggle, sold his farm and went to live with his son Rowland. In that year bush fires raged through the Benalla district, burning out many long-established settlers.

Antonio Ball appears to have lost his farm. He moved to a poorer part of town, did not close for the annual picnic or weekly half-holiday, and started taking court cases on very flimsy grounds for small amounts of money allegedly owing to him. He dispensed with the services of Mick Savage, and a few years later, sold up and left district.

The loss of his job was a bitter experience for Michael, who had just celebrated his 21st birthday. By 1893, nearly 30% of Victorian bread-winners were out of work. Those in work found their wages cut.

In mid-April 1893, Mick packed his few possessions into a swag and set out in search of work. When Rowland asked him what was going to do, his young brother replied, ‘Anything from pitch and toss to manslaughter’. ('Pitch and Toss' was the old name for 'Two-Up')

There was no point going to Melbourne, where two fifths of the Victorian population lived. Deep in depression, the city that a few years before had been ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ was by 1893 a hell-hole. Children were abandoned and babies killed by distraught parents. The people were emaciated, destitute, and hopeless.

Mick headed north across the Murray River to the Riverina district of New South Wales. He caught rabbits, brewed his billy, slept in hollow trees, and tramped in search of work. In later years Michael Joseph Savage looked back on these experiences and said they provided education for understanding men and women and the real meaning of life.

Michael walked to North Yanco Station, North of Narrandera, and laboured there for the next seven years. Labourers were at the very bottom of the social hierarchy. In 1896 an overseer at North Yanco was charged with assaulting an elderly labourer who had complained about the food. The overseer was acquitted by the local Justices of the Peace, on the grounds that ‘a little violence was necessary to preserve law and order’. Michael joined the new Australian Workers Union. Samuel McCaughey, who disliked employees who were Catholic or unionists, bought North Yanco in 1898. Michael Savage left in 1900.

He returned to Victoria and became a miner at Rutherglen on the Murray River. Often up to the waist in icy water, with only candle light in the dark and putrid air, men who refused to stay underground for nine hours were dismissed. The miner’s health and safety were of little importance to the owners. One manager was removed allegedly because he placed the lives of his men before the shareholders money.

Savage decided he would rather be on the ground pumping out the water than underground working in it. With mechanical experience from ‘tumbling tommies’ (revolving earth-scoops) and water pumps at North Yanco, he studied for a certificate as a mining and factory engineer. He received a first class certificate without qualification or condition, and found work with better pay and conditions. However he was sacked for refusing to work a pump with badly frayed ropes, which endangered the miners. He became increasingly involved in the Political Labour Party and he organised a co-operative bakery in Rutherglen.

In 1906 there was an election for the federal seat of Indi, encompassing Rutherglen, Wangaratta, Benalla and Beechworth. Since federation it had been represented by Isaac Isaacs. He resigned from politics in order to accept appointment to the High Court, throwing the seat open.

Nomination for the Political Labour Party was a contest between Michael Savage and Daniel Turnbull, a Talgarno farmer. Older and wealthier than Savage, Turnbull was chairman of the local mining board, and long-time councillor and president of the Beechworth shire. Each addressed the meeting for 20 minutes before voting took place. Turnbull beat Savage by one vote.

Savage worked hard for Turnbull, canvassing door to door and organising meetings. When Turnbull failed to turn up at Wahgunyah, Savage spoke for him. In the event only half the electors on the roll voted and Turnbull didn’t get in. It was said that Turnbull was a weak candidate, and a good labour man would have got in; in 1910 Labour did take the seat of Indi.

Savage and his colleagues turned their attention to the state electorate of Wangaratta and Rutherglen. Savage was looked on as certain for candidate. Organisation was well under way when the Premier, Thomas Bent, moved the election date from June to mid-March, with nominations to close in a fortnight. The money to cope with this could not be found, and Savage had to stand down.

In 1907, aged 35, Michael Savage set off for

New Zealand, yielding to the entreaties of a good friend who had

gone there. He found work at a brewery which had just acquired a

steam-engine, and needed a mechanic and engineer.

He

quickly became involved in the labour party, and in time became

a city councillor, MP for Auckland West, deputy leader of the

labour party, leader of the opposition, and from the 1935 till

his death in 1940 was Prime Minister of New Zealand.

He

quickly became involved in the labour party, and in time became

a city councillor, MP for Auckland West, deputy leader of the

labour party, leader of the opposition, and from the 1935 till

his death in 1940 was Prime Minister of New Zealand.

He visited Australia only once, in 1926, as representative for an Empire Parliamentary Conference. Over three months he toured the country, and found time to visit family and friends at Griffith, Wahgunyah and Benalla.

He never married. Political rivals claimed that Savage had deserted a wife and from 5 to 7 children back in Australia. When told of this Savage laughed and said, “I hope she turns up with all the kids – I’d love them all.” In 1938 it was said that rivals paid women to go from door to door stating that Savage was a non-naturalised Czechoslovakian.

Towards the end of his life he knew he was suffering from bowel cancer, but refused to be operated upon as the time taken for recovery would have destroyed his political work. He chose certain death.

Revered by many New Zealanders, some have made

the trek back to his birthplace… where he is barely known.

But for one vote, he might have won the seat of Indi in 1906,

and become a revered politician of Australia instead of New

Zealand.

A plaque commemorating

Michael Savage, and an Information Board,

can be found on the Samaria Rd, about 16km South of Benalla

(just south of the Knight Rd intersection).

The place is at the head of the now disused "Savage's Lane",

and to the East can be seen the trees which stand where the

Savage's cottage once was.

Please respect that the cottage site is on private property.

Return to Tatong Heritage Group Home Page

Contact us via tatongheritage at yahoo.com.au